Though we have seen a quantity of completely different robotic water striders through the years, scientists are nonetheless discovering intelligent new facets of the bugs to copy. Not too long ago, as an illustration, researchers created a strider-bot that zips throughout the water’s floor by way of followers on its toes.

Measuring solely 3 mm lengthy, water striders of the genus Rhagovelia actually are one thing particular.

On the ends of their two lengthy center legs – that are those they use for propulsion – there are feathery appendages which fan out upon hitting the water’s floor. Because the legs are then drawn again on the ahead stroke, these now-underwater followers cup the water just like the webs between a frog’s toes, quickly rowing the insect ahead.

Upon being drawn up out of the water on the finish of the stroke, the moist strands of the fan wick collectively into a degree – form of just like the bristles of a freshly dipped paintbrush. This makes the appendage extra streamlined because the leg swings again ahead, on its method to execute one other stroke.

Victor Ortega-Jimenez/UC Berkeley

The followers permit the bugs to shoot throughout the floor at speeds of roughly 120 physique lengths per second. What’s extra, by deploying a single water-grabbing fan on only one facet, the striders can pull off 90-degree turns in about 50 milliseconds.

For sure, in case you had been designing aquatic robots, it could be nice if they had been so agile. With that thought in thoughts, scientists from the College of California-Berkeley, Korea’s Ajou College, and the Georgia Institute of Expertise determined to take a more in-depth take a look at Rhagovelia.

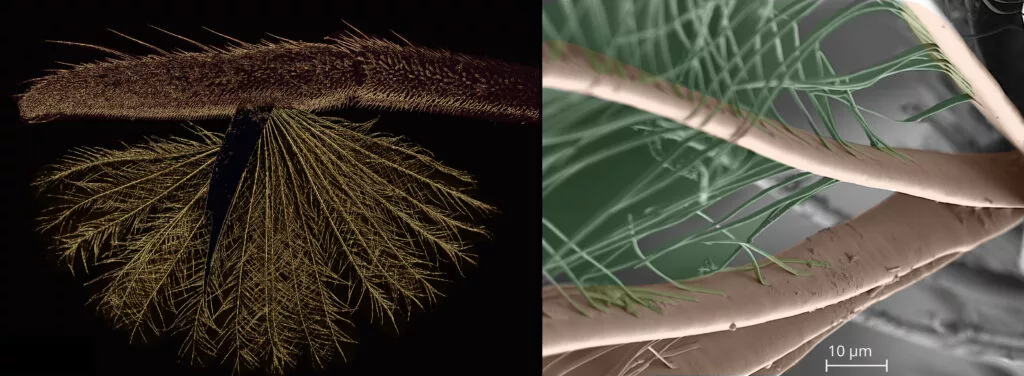

Using electron microscopy, Ajou’s Prof. Je-Sung Koh and postdoctoral researcher Dongjin Kim discovered that the person strands of every fan include a central flat, versatile, ribbon-like strip with smaller barbules branching off the edges of it – it truly is rather a lot like a feather. This design permits the appendages to fan out underwater, to allow them to be used like an oar.

Emma Perry/Univ. of Maine and Victor Ortega-Jimenez/UC Berkeley

The scientists moreover found that the water’s floor stress gives all of the elastic drive that’s wanted to trigger the strands to fan out. It had beforehand been assumed that the fanning motion was muscle-powered. A small quantity of muscle energy is utilized to carry the followers tense through the stroke, however none is used to deploy them.

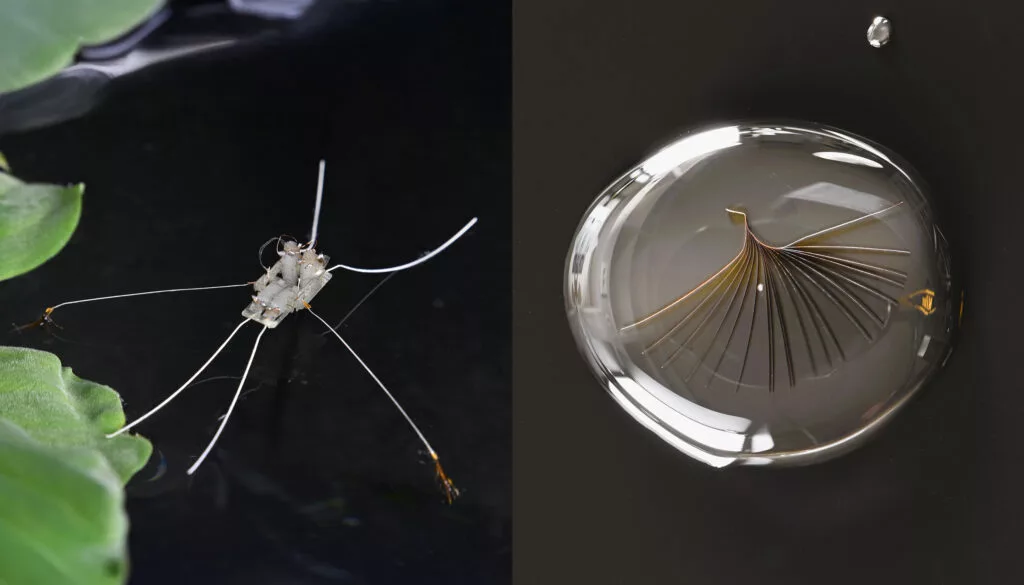

Based mostly on these findings, the crew created a robotic model of the insect, named Rhagobot.

It is definitely larger than its namesake, coming in at 8 cm lengthy by 10 cm broad by 1.5 cm excessive (3.1 by 3.9 by 0.6 in). On the finish of every of its two center legs is a 1-milligram Rhagovelia-like fan – full with the flat-ribbon microarchitecture – measuring 10 by 5 mm.

Ajou College, South Korea

The entire bot, which is hardwired to an exterior energy supply, weighs simply one-fifth of a gram. It is presently able to scooting throughout the water’s floor at two physique lengths per second, and making 90-degree turns in lower than half a second. It’s hoped that descendants of Rhagobot can be even quicker and extra agile, making them helpful in purposes resembling search-and-rescue or environmental monitoring.

“Our robotic followers self-morph utilizing nothing however water floor forces and versatile geometry, similar to their organic counterparts,” says Prof. Koh, senior co-author of the examine together with Georgia Tech’s Prof. Saad Bhamla. “It’s a type of mechanical embedded intelligence refined by nature by way of thousands and thousands of years of evolution. In small-scale robotics, these sorts of environment friendly and distinctive mechanisms can be a key enabling know-how for overcoming limits in miniaturization of standard robots.”

A paper on the analysis, which was led by UC Berkeley’s Asst. Prof. Ortega-Jiménez, was not too long ago printed within the journal Science. You may see Rhagobot in motion, within the video beneath.

Water Bugs, and a New Robotic, Use Fan-like Propellers

Sources: UC Berkeley, Georgia Tech